Peak oil

Peak oil is the point in time when the maximum rate of global petroleum extraction is reached, after which the rate of production enters terminal decline. This concept is based on the observed production rates of individual oil wells, and the combined production rate of a field of related oil wells. The aggregate production rate from an oil field over time usually grows exponentially until the rate peaks and then declines—sometimes rapidly—until the field is depleted. This concept is derived from the Hubbert curve, and has been shown to be applicable to the sum of a nation’s domestic production rate, and is similarly applied to the global rate of petroleum production. Peak oil is often confused with oil depletion; peak oil is the point of maximum production while depletion refers to a period of falling reserves and supply.

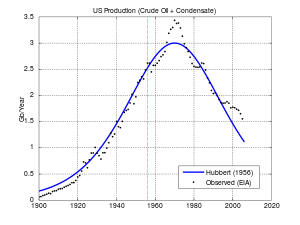

M. King Hubbert created and first used the models behind peak oil in 1956 to accurately predict that United States oil production would peak between 1965 and 1970.[1] His logistic model, now called Hubbert peak theory, and its variants have described with reasonable accuracy the peak and decline of production from oil wells, fields, regions, and countries,[2] and has also proved useful in other limited-resource production-domains. According to the Hubbert model, the production rate of a limited resource will follow a roughly symmetrical logistic distribution curve (sometimes incorrectly compared to a bell-shaped curve) based on the limits of exploitability and market pressures. Various modified versions of his original logistic model are used, using more complex functions to allow for real world factors. While each version is applied to a specific domain, the central features of the Hubbert curve (that production stops rising and then declines) remain unchanged, albeit with different profiles.

Some observers, such as petroleum industry experts Kenneth S. Deffeyes and Matthew Simmons, believe the high dependence of most modern industrial transport, agricultural, and industrial systems on the relative low cost and high availability of oil will cause the post-peak production decline and possible severe increases in the price of oil to have negative implications for the global economy. Predictions vary greatly as to what exactly these negative effects would be. If political and economic changes only occur in reaction to high prices and shortages rather than in reaction to the threat of a peak, then the degree of economic damage to importing countries will largely depend on how rapidly oil imports decline post-peak. According to the Export Land Model, oil exports drop much more quickly than production drops due to domestic consumption increases in exporting countries. Supply shortfalls would cause the price of oil to increase sharply, unless demand is mitigated with planned conservation measures and use of alternatives.[3]

Optimistic estimations of peak production forecast the global decline will begin by 2020 or later, and assume major investments in alternatives will occur before a crisis, without requiring major changes in the lifestyle of heavily oil-consuming nations. These models show the price of oil at first escalating and then retreating as other types of fuel and energy sources are used.[4] Pessimistic predictions of future oil production operate on the thesis that either the peak has already occurred,[5][6][7][8] that oil production is on the cusp of the peak, or that it will occur shortly.[9][10] As proactive mitigation may no longer be an option, a global depression is predicted, perhaps even initiating a chain reaction of the various feedback mechanisms in the global market that might stimulate a collapse of global industrial civilization, potentially leading to large population declines within a short period. Throughout the first two quarters of 2008, there were signs that a global recession was being made worse by a series of record oil prices.[11]

Demand for oil

The demand side of peak oil is concerned with the consumption over time, and the growth of this demand. World crude oil demand grew an average of 1.76% per year from 1994 to 2006, with a high of 3.4% in 2003-2004. World demand for oil is projected to increase 37% over 2006 levels by 2030 (118 million barrels per day (18.8×106 m3/d) from 86 million barrels (13.7×106 m3)), due in large part to increases in demand from the transportation sector.[12][13] A study published in the journal Energy Policy predicted demand would surpass supply by 2015 (unless constrained by strong recession pressures caused by reduced supply).[10]

Energy demand is distributed amongst four broad sectors: transportation, residential, commercial, and industrial.[14][15] In terms of oil use, transportation is the largest sector and the one that has seen the largest growth in demand in recent decades. This growth has largely come from new demand for personal-use vehicles powered by internal combustion engines.[16] This sector also has the highest consumption rates, accounting for approximately 68.9% of the oil used in the United States in 2006,[17] and 55% of oil use worldwide as documented in the Hirsch report. Transportation is therefore of particular interest to those seeking to mitigate the effects of peak oil.

Although demand growth is highest in the developing world,[18] the United States is the world's largest consumer of petroleum. Between 1995 and 2005, U.S. consumption grew from 17.7 million barrels a day to 20.7 million barrels a day, a 3 million barrel a day increase. China, by comparison, increased consumption from 3.4 million barrels a day to 7 million barrels a day, an increase of 3.6 million barrels a day, in the same time frame.[19]

As countries develop, industry, rapid urbanization, and higher living standards drive up energy use, most often of oil. Thriving economies such as China and India are quickly becoming large oil consumers.[20] China has seen oil consumption grow by 8% yearly since 2002, doubling from 1996-2006.[18] In 2008, auto sales in China were expected to grow by as much as 15-20%, resulting in part from economic growth rates of over 10% for 5 years in a row.[21]

Although swift continued growth in China is often predicted, others predict that China's export dominated economy will not continue such growth trends due to wage and price inflation and reduced demand from the United States.[22] India's oil imports are expected to more than triple from 2005 levels by 2020, rising to 5 million barrels per day (790×103 m3/d).[23]

The International Energy Agency estimated in January 2009 that oil demand fell in 2008 by 0.3%, and that it would fall by 0.6% in 2009. Oil consumption had not fallen for two years in a row since 1982-1983.[24]

The Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimated that the United States' demand for petroleum-based transportation fuels fell 7.1% in 2008, which is "the steepest one-year decline since at least 1950." The agency stated that gasoline usage in the United States may have peaked in 2007, in part due to increasing interest in and mandates for use of biofuels and energy efficiency.[25]

The IEA now expects global oil demand to increase by about 1.6 million barrels a day in 2010. Asian economies, in particular China, will lead the increase.[26] China’s oil demand may rise more than 5% compared with a 3.7% gain in 2009, the CNPC said.[27]

Population

Another significant factor on petroleum demand has been human population growth. Oil production per capita peaked in the 1970s.[28] The United States Census Bureau predicts that the world population in 2030 will be almost double that of 1980.[29] Author Matt Savinar predicts that oil production in 2030 will have declined back to 1980 levels as worldwide demand for oil significantly out-paces production.[30][31] Physicist Albert Bartlett claims that the rate of oil production per capita is falling, and that the decline has gone undiscussed because a politically incorrect form of population control may be implied by mitigation.[32]

Oil production per capita has declined from 5.26 barrels per year (0.836 m3/a) in 1980 to 4.44 barrels per year (0.706 m3/a) in 1993,[29][33] but then increased to 4.79 barrels per year (0.762 m3/a) in 2005.[29][33] In 2006, the world oil production took a downturn from 84.631 to 84.597 million barrels per day (13.4553×106 to 13.4498×106 m3/d) although population has continued to increase. This has caused the oil production per capita to drop again to 4.73 barrels per year (0.752 m3/a).[29][33]

One factor that has so far helped ameliorate the effect of population growth on demand is the decline of population growth rate since the 1970s, although this is offset to a degree by increasing average longevity in developed nations. In 1970, the population grew at 2.1%. By 2007, the growth rate had declined to 1.167%.[34] However, oil production is still outpacing population growth to meet demand. World population grew by 6.2% from 6.07 billion in 2000 to 6.45 billion in 2005,[29] whereas according to BP, global oil production during that same period increased from 74.9 to 81.1 million barrels (11.91×106 to 12.89×106 m3), or by 8.2%.[35] or according to EIA, from 77.762 to 84.631 million barrels (12.3632×106 to 13.4553×106 m3), or by 8.8%.[33]

Agricultural effects and population limits

Since supplies of oil and gas are essential to modern agriculture techniques, a fall in global oil supplies could cause spiking food prices and unprecedented famine in the coming decades.[36][note 1] Geologist Dale Allen Pfeiffer contends that current population levels are unsustainable, and that to achieve a sustainable economy and avert disaster the United States population would have to be reduced by at least one-third, and world population by two-thirds.[37]

The largest consumer of fossil fuels in modern agriculture is ammonia production (for fertilizer) via the Haber process, which is essential to high-yielding intensive agriculture. The specific fossil fuel input to fertilizer production is primarily natural gas, to provide hydrogen via steam reforming. Given sufficient supplies of renewable electricity, hydrogen can be generated without fossil fuels using methods such as electrolysis. For example, the Vemork hydroelectric plant in Norway used its surplus electricity output to generate renewable ammonia from 1911 to 1971.[38]

Iceland currently generates ammonia using the electrical output from its hydroelectric and geothermal power plants, because Iceland has those resources in abundance while having no domestic hydrocarbon resources, and a high cost for importing natural gas.[39] However, in the near term, almost every large-scale source of renewable energy still requires petroleum inputs, such as to fuel construction equipment and to transport workers and materials. Iceland, for example, has abundant renewable energy resources, but still depends critically on liquid fuels from petroleum, all of which it must import. If the supply of petroleum should fall faster than people can learn how to build renewable energy infrastructure using only renewable inputs, it may not be possible to maintain the intensive agriculture necessary to support the high global population.

Petroleum supply

Discoveries

| “ | All the easy oil and gas in the world has pretty much been found. Now comes the harder work in finding and producing oil from more challenging environments and work areas. | ” |

|

— William J. Cummings, Exxon-Mobil company spokesman, December 2005[40]

|

| “ | It is pretty clear that there is not much chance of finding any significant quantity of new cheap oil. Any new or unconventional oil is going to be expensive. | ” |

|

— Lord Ron Oxburgh, a former chairman of Shell, October 2008[41]

|

To pump oil, it first needs to be discovered. The peak of world oilfield discoveries occurred in 1965[42] at around 55 billion barrels(Gb)/year.[43] According to the Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas (ASPO), the rate of discovery has been falling steadily since. Less than 10 Gb/yr of oil were discovered each year between 2002-2007.[44]

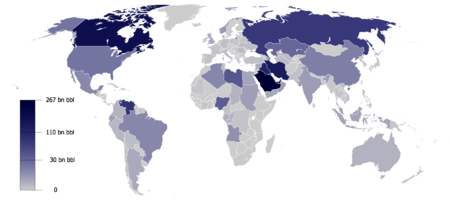

Reserves

Total possible conventional crude oil reserves include all crude oil with 90-95% certainty of being technically possible to produce (from reservoirs through a wellbore using primary, secondary, improved, enhanced, or tertiary methods), all crude with a 50% probability of being produced in the future, and discovered reserves which have a 5-10% possibility of being produced in the future. These are referred to as 1P/Proven (90-95%), 2P/Probable (50%), and 3P/Possible (5-10%).[45] This does not include liquids extracted from mined solids or gasses (oil sands, oil shales, gas-to-liquid processes, or coal-to-liquid processes).[46]

Many current 2P calculations predict reserves to be between 1150-1350 Gb, but because of misinformation, withheld information, and misleading reserve calculations, it has been reported that 2P reserves are likely nearer to 850-900 Gb.[6][10] Reserves in effect peaked in 1980, when production first surpassed new discoveries, though creative methods of recalculating reserves have made this difficult to establish exactly.[6]

Current technology is capable of extracting about 40% of the oil from most wells. Some speculate that future technology will make further extraction possible,[47] but this future technology is usually already considered in Proven and Probable (2P) reserve numbers.

In many major producing countries, the majority of reserves claims have not been subject to outside audit or examination. Most of the easy-to-extract oil has been found.[40] Recent price increases have led to oil exploration in areas where extraction is much more expensive, such as in extremely deep wells, extreme downhole temperatures, and environmentally sensitive areas or where high technology will be required to extract the oil. A lower rate of discoveries per explorations has led to a shortage of drilling rigs, increases in steel prices, and overall increases in costs due to complexity.[48][49]

Concerns over stated reserves

| “ | [World] reserves are confused and in fact inflated. Many of the so-called reserves are in fact resources. They're not delineated, they're not accessible, they’re not available for production. | ” |

Al-Husseini estimated that 300 billion barrels (48×109 m3) of the world's 1,200 billion barrels (190×109 m3) of proven reserves should be recategorized as speculative resources.[7]

One difficulty in forecasting the date of peak oil is the opacity surrounding the oil reserves classified as 'proven'. Many worrying signs concerning the depletion of proven reserves have emerged in recent years.[50][51] This was best exemplified by the 2004 scandal surrounding the 'evaporation' of 20% of Shell's reserves.[52]

For the most part, proven reserves are stated by the oil companies, the producer states and the consumer states. All three have reasons to overstate their proven reserves: oil companies may look to increase their potential worth; producer countries gain a stronger international stature; and governments of consumer countries may seek a means to foster sentiments of security and stability within their economies and among consumers.

The Energy Watch Group (EWG) 2007 report shows total world Proved (P95) plus Probable (P50) reserves to be between 854 billion and 1,255 billion barrels (30 to 40 years of supply if demand growth were to stop immediately). Major discrepancies arise from accuracy issues with OPEC's self-reported numbers. Besides the possibility that these nations have overstated their reserves for political reasons (during periods of no substantial discoveries), over 70 nations also follow a practice of not reducing their reserves to account for yearly production. 1,255 billion barrels is therefore a best-case scenario.[6] Analysts have suggested that OPEC member nations have economic incentives to exaggerate their reserves, as the OPEC quota system allows greater output for countries with greater reserves.[47]

Kuwait, for example, was reported in the January 2006 issue of Petroleum Intelligence Weekly to have only 48 billion barrels in reserve, of which only 24 were fully proven. This report was based on the leak of a confidential document from Kuwait and has not been formally denied by the Kuwaiti authorities. This leaked document is from 2001,[53] so the figure includes oil that has been produced since 2001, roughly 5-6 billion barrels,[19] but excludes revisions or discoveries made since then. Additionally, the reported 1.5 billion barrels of oil burned off by Iraqi soldiers in the First Persian Gulf War[54] are conspicuously missing from Kuwait's figures.

On the other hand, investigative journalist Greg Palast argues that oil companies have an interest in making oil look more rare than it is, to justify higher prices.[55] This view is refuted by ecological journalist Richard Heinberg.[56] Other analysts argue that oil producing countries understate the extent of their reserves to drive up the price.[57]

In November 2009, a senior official at the IEA alleged that the United States had encouraged the international agency to manipulate depletion rates and future reserve data to maintain lower oil prices.[58] In 2005, the IEA predicted that 2030 production rates would reach 120 million barrels per day, but this number was gradually reduced to 105 million barrels per day. The IEA official alleged industry insiders agree that even 90 to 95 million barrels per day might be impossible to achieve. Although many outsiders had questioned the IEA numbers in the past, this was the first time an insider had raised the same concerns.[58] A 2008 analysis of IEA predictions questioned several underlying assumptions and claimed that a 2030 production level of 75 million barrels per day (comprising 55 million barrels of crude oil and 20 million barrels of both non-conventional oil and natural gas liquids) was more realistic than the IEA numbers.[8]

Unconventional sources

Unconventional sources, such as heavy crude oil, oil sands, and oil shale are not counted as part of oil reserves. However, with rule changes by the SEC,[59] oil companies can now book them as proven reserves after opening a strip mine or thermal facility for extraction. These unconventional sources are more labor and resource intensive to produce, however, requiring extra energy to refine, resulting in higher production costs and up to three times more greenhouse gas emissions per barrel (or barrel equivalent) on a "well to tank" basis or 10 to 45% more on a "well to wheels" basis, which includes the carbon emitted from combustion of the final product.[60][61]

While the energy used, resources needed, and environmental effects of extracting unconventional sources has traditionally been prohibitively high, the three major unconventional oil sources being considered for large scale production are the extra heavy oil in the Orinoco Belt of Venezuela,[62] the Athabasca Oil Sands in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin,[63] and the oil shales of the Green River Formation in Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming in the United States.[64][65] Energy companies such Syncrude and Suncor have been extracting bitumen for decades but production has increased greatly in recent years with the development of Steam Assisted Gravity Drainage and other extraction technologies.[66]

Chuck Masters of the USGS estimates that, "Taken together, these resource occurrences, in the Western Hemisphere, are approximately equal to the Identified Reserves of conventional crude oil accredited to the Middle East."[67] Authorities familiar with the resources believe that the world's ultimate reserves of unconventional oil are several times as large as those of conventional oil and will be highly profitable for companies as a result of higher prices in the 21st century.[68] In October 2009, the USGS updated the Orinoco tar sands (Venezuela) recoverable "mean value" to 513 billion barrels (8.16×1010 m3), with a 90% chance of being within the range of 380-652 billion barrels, making this area "one of the world's largest recoverable oil accumulations".[69]

Despite the large quantities of oil available in non-conventional sources, Matthew Simmons argues that limitations on production prevent them from becoming an effective substitute for conventional crude oil. Simmons states that "these are high energy intensity projects that can never reach high volumes" to offset significant losses from other sources.[71] Another study claims that even under highly optimistic assumptions, "Canada's oil sands will not prevent peak oil," although production could reach 5 million bbl/day by 2030 in a "crash program" development effort.[72]

Moreover, oil extracted from these sources typically contains contaminants such as sulfur and heavy metals that are energy-intensive to extract and can leave tailings - ponds containing hydrocarbon sludge - in some cases.[60][73] The same applies to much of the Middle East's undeveloped conventional oil reserves, much of which is heavy, viscous, and contaminated with sulfur and metals to the point of being unusable.[74] However, recent high oil prices make these sources more financially appealing.[47] A study by Wood Mackenzie suggests that within 15 years all the world’s extra oil supply will likely come from unconventional sources.[75]

Synthetic sources

A 2003 article in Discover magazine claimed that thermal depolymerization could be used to manufacture oil indefinitely, out of garbage, sewage, and agricultural waste. The article claimed that the cost of the process was $15 per barrel.[76] A follow-up article in 2006 stated that the cost was actually $80 per barrel, because the feedstock that had previously been considered as hazardous waste now had market value.[77]

A 2007 news bulletin published by Los Alamos Laboratory proposed that hydrogen (possibly produced using hot fluid from nuclear reactors to split water into hydrogen and oxygen) in combination with sequestered CO2 could be used to produce methanol, which could then be converted into gasoline. The press release stated that in order for such a process to be economically feasible, gasoline prices would need to be above $4.60 "at the pump" in U.S. markets. Capital and operational costs were uncertain mostly because the costs associated with sequestering CO2 are unknown.[78]

Production

The point in time when peak global oil production occurs defines peak oil. This is because production capacity is the main limitation of supply. Therefore, when production decreases, it becomes the main bottleneck to the petroleum supply/demand equation.

World wide oil discoveries have been less than annual production since 1980.[6] According to several sources, worldwide production is past or near its maximum.[5][6][7][9] World population has grown faster than oil production. Because of this, oil production per capita peaked in 1979 (preceded by a plateau during the period of 1973-1979).[28]

The increasing investment in harder-to-reach oil is a sign of oil companies' belief in the end of easy oil.[40] Additionally, while it is widely believed that increased oil prices spur an increase in production, an increasing number of oil industry insiders are now coming to believe that even with higher prices, oil production is unlikely to increase significantly beyond its current level. Among the reasons cited are both geological factors as well as "above ground" factors that are likely to see oil production plateau near its current level.[79]

Recent work points to the difficulty of increasing production even with vastly increased investment in exploration and production, at least in mature petroleum regions. A 2008 Journal of Energy Security analysis of the energy return on drilling effort in the United States points to an extremely limited potential to increase production of both gas and (especially) oil. By looking at the historical response of production to variation in drilling effort, this analysis showed very little increase of production attributable to increased drilling. This was due to a tight quantitative relationship of diminishing returns with increasing drilling effort: as drilling effort increased, the energy obtained per active drill rig was reduced according to a severely diminishing power law. This fact means that even an enormous increase of drilling effort is unlikely to lead to significantly increased oil and gas production in a mature petroleum region like the United States.[80]

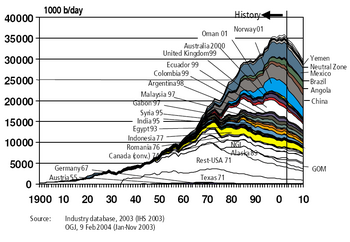

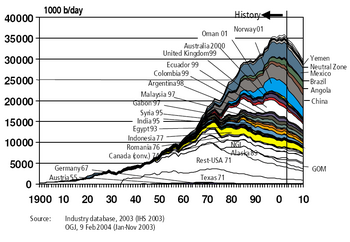

Worldwide production trends

World oil production growth trends were flat from 2005 to 2008. According to a January 2007 International Energy Agency report, global supply (which includes biofuels, non-crude sources of petroleum, and use of strategic oil reserves, in addition to crude production) averaged 85.24 million barrels per day (13.552×106 m3/d) in 2006, up 0.76 million barrels per day (121×103 m3/d) (0.9%), from 2005.[81] Average yearly gains in global supply from 1987 to 2005 were 1.2 million barrels per day (190×103 m3/d) (1.7%).[81] In 2008, the IEA drastically increased its prediction of production decline from 3.7% a year to 6.7% a year, based largely on better accounting methods, including actual research of individual oil field production through out the world.[82]

Oil field decline

Of the largest 21 fields, at least 9 are in decline.[83] In April, 2006, a Saudi Aramco spokesman admitted that its mature fields are now declining at a rate of 8% per year (with a national composite decline of about 2%).[84] This information has been used to argue that Ghawar, which is the largest oil field in the world and responsible for approximately half of Saudi Arabia's oil production over the last 50 years, has peaked.[47][85] The world's second largest oil field, the Burgan field in Kuwait, entered decline in November 2005.[86]

According to a study of the largest 811 oilfields conducted in early 2008 by Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA), the average rate of field decline is 4.5% per year. The IEA stated in November 2008 that an analysis of 800 oilfields showed the decline in oil production to be 6.7% a year, and that this would grow to 8.6% in 2030.[87] There are also projects expected to begin production within the next decade that are hoped to offset these declines. The CERA report projects a 2017 production level of over 100 million barrels per day (16×106 m3/d).[88]

Kjell Aleklett of the Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas agrees with their decline rates, but considers the rate of new fields coming online—100% of all projects in development, but with 30% of them experiencing delays, plus a mix of new small fields and field expansions—overly optimistic.[89] A more rapid annual rate of decline of 5.1% in 800 of the world's largest oil fields was reported by the International Energy Agency in their World Energy Outlook 2008.[90]

Mexico announced that its giant Cantarell Field entered depletion in March, 2006,[91] due to past overproduction. In 2000, PEMEX built the largest nitrogen plant in the world in an attempt to maintain production through nitrogen injection into the formation,[92] but by 2006, Cantarell was declining at a rate of 13% per year.[93]

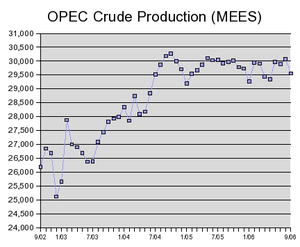

OPEC had vowed in 2000 to maintain a production level sufficient to keep oil prices between $22–28 per barrel, but did not prove possible. In its 2007 annual report, OPEC projected that it could maintain a production level that would stabilize the price of oil at around $50–60 per barrel until 2030.[94] On November 18, 2007, with oil above $98 a barrel, King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia, a long-time advocate of stabilized oil prices, announced that his country would not increase production to lower prices.[95] Saudi Arabia's inability, as the world's largest supplier, to stabilize prices through increased production during that period suggests that no nation or organization had the spare production capacity to lower oil prices. The implication is that those major suppliers who had not yet peaked were operating at or near full capacity.[47]

Commentators have pointed to the Jack 2 deep water test well in the Gulf of Mexico, announced 5 September 2006,[96] as evidence that there is no imminent peak in global oil production. According to one estimate, the field could account for up to 11% of U.S. production within seven years.[97] However, even though oil discoveries are expected after the peak oil of production is reached,[98] the new reserves of oil will be harder to find and extract. The Jack 2 field, for instance, is more than 20,000 feet (6,100 m) under the sea floor in 7,000 feet (2,100 m) of water, requiring 8.5 kilometers of pipe to reach. Additionally, even the maximum estimate of 15 billion barrels (2.4×109 m3) represents slightly less than 2 years of U.S. consumption at present levels.[15]

Control over supply

Entities such as governments or cartels can reduce supply to the world market by limiting access to the supply through nationalizing oil, cutting back on production, limiting drilling rights, imposing taxes, etc. International sanctions, corruption, and military conflicts can also reduce supply.

Nationalization of oil supplies

Another factor affecting global oil supply is the nationalization of oil reserves by producing nations. The nationalization of oil occurs as countries begin to deprivatize oil production and withhold exports. Kate Dourian, Platts' Middle East editor, points out that while estimates of oil reserves may vary, politics have now entered the equation of oil supply. "Some countries are becoming off limits. Major oil companies operating in Venezuela find themselves in a difficult position because of the growing nationalization of that resource. These countries are now reluctant to share their reserves."[99]

According to consulting firm PFC Energy, only 7% of the world's estimated oil and gas reserves are in countries that allow companies like ExxonMobil free rein. Fully 65% are in the hands of state-owned companies such as Saudi Aramco, with the rest in countries such as Russia and Venezuela, where access by Western companies is difficult. The PFC study implies political factors are limiting capacity increases in Mexico, Venezuela, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, and Russia. Saudi Arabia is also limiting capacity expansion, but because of a self-imposed cap, unlike the other countries.[100] As a result of not having access to countries amenable to oil exploration, ExxonMobil is not making nearly the investment in finding new oil that it did in 1981.[101]

Cartel influence on supply

OPEC is an alliance between 12 diverse oil producing countries (Algeria, Angola, Ecuador, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Nigeria, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Venezuela) to control the supply of oil. OPEC's power was consolidated as various countries nationalized their oil holdings, and wrested decision-making away from the "Seven Sisters," (Anglo-Iranian, Socony-Vacuum, Royal Dutch Shell, Gulf, Esso, Texaco, and Socal) and created their own oil companies to control the oil. OPEC tries to influence prices by restricting production. It does this by allocating each member country a quota for production. All 12 members agree to keep prices high by producing at lower levels than they otherwise would. There is no way to verify adherence to the quota, so every member faces the same incentive to ‘cheat’ the cartel.[102] Washington kept the oil flowing and gained favorable OPEC policies mainly by arming, and propping up Saudi regimes. According to some, the purpose for the second Iraq war is to break the back of OPEC and return control of the oil fields to western oil companies.[103]

Alternately, commodities trader Raymond Learsy, author of Over a Barrel: Breaking the Middle East Oil Cartel, contends that OPEC has trained consumers to believe that oil is a much more finite resource than it is. To back his argument, he points to past false alarms and apparent collaboration.[57] He also believes that peak oil analysts are conspiring with OPEC and the oil companies to create a "fabricated drama of peak oil" to drive up oil prices and profits. It is worth noting oil had risen to a little over $30/barrel at that time. A counter-argument was given in the Huffington Post after he and Steve Andrews, co-founder of ASPO, debated on CNBC in June 2007.[104]

Timing of peak oil

M. King Hubbert initially predicted in 1974 that peak oil would occur in 1995 "if current trends continue."[105] However, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, global oil consumption actually dropped (due to the shift to energy-efficient cars,[106] the shift to electricity and natural gas for heating,[107] and other factors), then rebounded to a lower level of growth in the mid 1980s. Thus oil production did not peak in 1995, and has climbed to more than double the rate initially projected. This underscores the fact that the only reliable way to identify the timing of peak oil will be in retrospect. However, predictions have been refined through the years as up-to-date information becomes more readily available, such as new reserve growth data.[108] Predictions of the timing of peak oil include the possibilities that it has recently occurred, that it will occur shortly, or that a plateau of oil production will sustain supply for up to 100 years. None of these predictions dispute the peaking of oil production, but disagree only on when it will occur.

According to Matthew Simmons, Chairman of Simmons & Company International and author of Twilight in the Desert: The Coming Saudi Oil Shock and the World Economy, "...peaking is one of these fuzzy events that you only know clearly when you see it through a rear view mirror, and by then an alternate resolution is generally too late."[109]

Pessimistic predictions of future oil production

Saudi Arabia's regent Abdullah told his subjects in 1998, "The oil boom is over and will not return... All of us must get used to a different lifestyle." Since then he has implemented a series of anti-corruption reforms and government programs intended to lower Saudi Arabia's dependence on oil revenues. The royal family was put on notice to end its history of excess and new industries were created to diversify the national economy.[110]

Matthew Simmons said on October 26, 2006 that global oil production may have peaked in December 2005, though he cautioned that further monitoring of production is required to determine if a peak has actually occurred.[111] In 2007, Kenneth S. Deffeyes also argued that world oil production had peaked in December 2005.[5]

The July 2007 IEA Medium-Term Oil Market Report projected a 2% non-OPEC liquids supply growth in 2007-2009, reaching 51.0 mb/d in 2008, receding thereafter as the slate of verifiable investment projects diminishes. They refer to this decline as a plateau. The report expects only a small amount of supply growth from OPEC producers, with 70% of the increase coming from Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Angola as security and investment issues continue to impinge on oil exports from Iraq, Nigeria and Venezuela.[112]

In October 2007, the Energy Watch Group, a German research group founded by MP Hans-Josef Fell, released a report claiming that oil production peaked in 2006 and would decline by several percent annually. The authors predicted negative economic effects and social unrest as a result.[6][113] They stated that the IEA production plateau prediction uses purely economic models, which rely on an ability to raise production and discovery rates at will.[6]

Sadad Al Husseini, former head of Saudi Aramco's production and exploration, stated in an October 29, 2007 interview that oil production had likely already reached its peak in 2006,[7] and that assumptions by the IEA and EIA of production increases by OPEC to over 45 MB/day are "quite unrealistic."[7] Data from the United States Energy Information Administration show that world production leveled out in 2004, and an October 2007 retrospective report by the Energy Watch Group concluded that this data showed the peak of conventional oil production in the third quarter of 2006.[6]

ASPO predicted in their January 2008 newsletter that the peak in all oil (including non-conventional sources), would occur in 2010. This is earlier than the July 2007 newsletter prediction of 2011.[114] ASPO Ireland in its May 2008 newsletter, number 89, revised its depletion model and advanced the date of the peak of overall liquids from 2010 to 2007.[115]

Texas alternative energy activist and oilman T. Boone Pickens stated in 2005 that worldwide conventional oil production was very close to peaking.[116] On June 17, 2008, in testimony before the U.S. Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, Pickens stated that "I do believe you have peaked out at 85 million barrels a day globally."[117]

At least one oil company, French supermajor Total S.A., announced plans in 2008 to shift their focus to nuclear energy instead of oil and gas. A Total senior vice president explained that this is because they believe oil production will peak before 2020, and they would like to diversify their position in the energy markets.[118]

The UK Industry Taskforce on Peak Oil and Energy Security (ITPOES) reported in late October 2008 that peak oil is likely to occur by 2013. ITPOES consists of eight companies: Arup, FirstGroup, Foster + Partners, Scottish and Southern Energy, Solarcentury, Stagecoach Group, Virgin Group, and Yahoo. Their report includes a chapter written by Shell corporation.[119]

In October 2009, a report published by the Government-supported UK Energy Research Centre, following 'a review of over 500 studies, analysis of industry databases and comparison of global supply forecasts', concluded that 'a peak in conventional oil production before 2030 appears likely and there is a significant risk of a peak before 2020'.[120] The authors believe this forecast to be valid 'despite the large uncertainties in the available data'.[121] The study was claimed to be the first to undertake an 'independent, thorough and systematic review of the evidence and arguments in the 'peak oil’ debate'.[122] The authors noted that 'forecasts that delay a peak in conventional oil production until after 2030 are at best optimistic and at worst implausible' and warn of the risk that 'rising oil prices will encourage the rapid development of carbon-intensive alternatives that will make it difficult or impossible to prevent dangerous climate change[122] and that 'early investment in low-carbon alternatives to conventional oil is of considerable importance' in avoiding this scenario.[123]

A 2010 report by Oxford University researchers in the journal Energy Policy predicted that production would peak before 2015.[10]

Optimistic predictions of future oil production

Non-'peakists' can be divided into several different categories based on their specific criticism of peak oil. Some claim that any peak will not come soon or have a dramatic effect on the world economies. Others claim we will not reach a peak for technological reasons, while still others claim our oil reserves are quickly regenerated abiotically.

Plateau oil

.jpg)

CERA, which counts unconventional sources in reserves while discounting EROEI, believes that global production will eventually follow an “undulating plateau” for one or more decades before declining slowly.[4] In 2005 the group predicted that "petroleum supplies will be expanding faster than demand over the next five years."[124]

In 2007, The Wall Street Journal reported that "a growing number of oil-industry chieftains" believed that oil production would soon reach a ceiling for a variety of reasons, and plateau at that level for some time. Several chief executives stated that projections of over 100 million barrels of production per day are unrealistic, contradicting the projections of the International Energy Agency and United States Energy Information Administration.[125]

In 2008, the IEA predicted a plateau by 2020 and a peak by 2030. The report called for a "global energy revolution" to prepare mitigations by 2020 and avoid "more difficult days" and large wealth transfers from OECD nations to oil producing nations.[82] This estimate was changed in 2009 to predict a peak by 2020, with severe supply-growth constraints beginning in 2010 (stemming from "patently unsustainable" energy use and a lack of production investment) leading to rapidly increasing oil prices and an "oil crunch" before the peak.[126]

It has been noted that even a "plateau oil" scenario may cause socio-political disruption through extreme petroleum price instability.[127]

Energy Information Administration and USGS 2000 reports

The United States Energy Information Administration projects (as of 2006) world consumption of oil to increase to 98.3 million barrels per day (15.63×106 m3/d) in 2015 and 118 million barrels per day (18.8×106 m3/d) in 2030.[128] This would require a more than 35 percent increase in world oil production by 2030. A 2004 paper by the Energy Information Administration based on data collected in 2000 disagrees with Hubbert peak theory on several points. It:[16]

- explicitly incorporates demand into model as well as supply

- does not assume pre/post-peak symmetry of production levels

- models pre- and post-peak production with different functions (exponential growth and constant reserves-to-production ratio, respectively)

- assumes reserve growth, including via technological advancement and exploitation of small reservoirs

The EIA estimates of future oil supply are countered by Sadad Al Husseini, a retired Vice President of Exploration of Aramco, who calls it a 'dangerous over-estimate'.[129] Husseini also points out that population growth and the emergence of China and India means oil prices are now going to be structurally higher than they have been.

Colin Campbell argues that the 2000 United States Geological Survey (USGS) estimates is a methodologically flawed study that has done incalculable damage by misleading international agencies and governments. Campbell dismisses the notion that the world can seamlessly move to more difficult and expensive sources of oil and gas when the need arises. He argues that oil is in profitable abundance or not there at all, due ultimately to the fact that it is a liquid concentrated by nature in a few places that possess the right geological conditions. Campbell believes OPEC countries raised their reserves to get higher oil quotas and to avoid internal critique. He also points out that the USGS failed to extrapolate past discovery trends in the world’s mature basins.[130]

No peak oil

The view that oil extraction will never enter a depletion phase is often referred to as "cornucopian" in ecology and sustainability literature.[131][132][133]

Abdullah S. Jum'ah, President, Director and CEO of Saudi Aramco states that the world has adequate reserves of conventional and nonconventional oil sources that will last for more than a century.[134][135] As recently as 2008 he pronounced "We have grossly underestimated mankind’s ability to find new reserves of petroleum, as well as our capacity to raise recovery rates and tap fields once thought inaccessible or impossible to produce.” Jum’ah believes that in-place conventional and non-conventional liquid resources may ultimately total between 13 trillion and 16 trillion barrels and that only a small fraction (1.1 trillion) has been extracted to date.[136]

| “ | I do not believe the world has to worry about ‘peak oil’ for a very long time. | ” |

|

— Abdullah S. Jum'ah, 2008-01[136]

|

Economist Michael Lynch says that the Hubbert Peak theory is flawed and that there is no imminent peak in oil production. He argued in 2004 that production is determined by demand as well as geology, and that fluctuations in oil supply are due to political and economic effects as well as the physical processes of exploration, discovery and production.[137] This idea is echoed by Jad Mouawad, who explains that as oil prices rise, new extraction technologies become viable, thus expanding the total recoverable oil reserves. This, according to Mouwad, is one explanation of the changes in peak production estimates.[138]

Leonardo Maugeri, group senior vice president, Corporate Strategies of Eni S.p.A., dismissed the peak oil thesis in a 2004 policy position piece in Science as "the current model of oil doomsters," and based on several flawed assumptions. He characterizes the peak oil theory as part of a series of "recurring oil panics" that have "driven Western political circles toward oil imperialism and attempts to assert direct or indirect control over oil-producing regions". Maugeri claims the geological structure of the earth has not been explored thoroughly enough to conclude that the declining trend in discoveries, which began in the 1960s, will continue. He goes on to claim that complete global oil production, discovery trends, and geological data are not available globally.[139]

Possible effects and consequences of peak oil

The wide use of fossil fuels has been one of the most important stimuli of economic growth and prosperity since the industrial revolution, allowing humans to participate in takedown, or the consumption of energy at a greater rate than it is being replaced. Some believe that when oil production decreases, human culture, and modern technological society will be forced to change drastically. The impact of peak oil will depend heavily on the rate of decline and the development and adoption of effective alternatives. If alternatives are not forthcoming, the products produced with oil (including fertilizers, detergents, solvents, adhesives, and most plastics) would become scarce and expensive.

The Hirsch report

In 2005, the United States Department of Energy published a report titled Peaking of World Oil Production: Impacts, Mitigation, & Risk Management.[140] Known as the Hirsch report, it stated, "The peaking of world oil production presents the U.S. and the world with an unprecedented risk management problem. As peaking is approached, liquid fuel prices and price volatility will increase dramatically, and, without timely mitigation, the economic, social, and political costs will be unprecedented. Viable mitigation options exist on both the supply and demand sides, but to have substantial impact, they must be initiated more than a decade in advance of peaking."

Conclusions from the Hirsch report and three scenarios

The Hirsch report came to a number of conclusions:

- World oil peaking is going to happen - some forecasters predict within a decade, others later.

- Oil peaking could cost economies dearly - particularly that of the U.S.

- Oil peaking presents a unique challenge - previous transitions were gradual and evolutionary; oil peaking will be abrupt and revolutionary.

- The real problem is liquid fuels for transportation - motor vehicles, aircraft, trains, and ships have no ready alternative.

- Mitigation efforts will require substantial time - an intense effort over decades.

- Both supply and demand will require attention - higher efficiency can reduce demand, but large amounts of substitute fuels must be produced.

- It is a matter of risk management - early mitigation will be less damaging than delayed mitigation.

- Government intervention will be required - otherwise the economic and social implications would be chaotic.

- Economic upheaval is not inevitable - without mitigation, peaking will cause major upheaval, but given enough lead-time, the problems are soluble.

- More information is needed - effective action requires better understanding of a number of issues.

The report listed three possible scenarios: waiting until world oil production peaks before taking crash program action leaves the world with a significant liquid fuel deficit for more than two decades; initiating a mitigation crash program ten years before world oil peaking helps considerably but still leaves a liquid fuels shortfall roughly a decade after the time that oil would have peaked; or initiating a mitigation crash program twenty years before peaking appears to offer the possibility of avoiding a world liquid fuels shortfall for the forecast period.

Other predictions

Export Land Model

The Export Land Model states that after peak oil petroleum exporting countries will be forced to reduce their exports more quickly than their production decreases because of internal demand growth. Countries that rely on imported petroleum will therefore be affected earlier and more dramatically than exporting countries.[141] Mexico is already in this situation. Internal consumption grew by 5.9% in 2006 in the five biggest exporting countries, and their exports declined by over 3%. It is estimated that by 2010 internal demand will decrease worldwide exports by 2.5 million barrels per day.[142]

Transportation and housing

A majority of Americans live in suburbs, a type of low-density settlement designed around universal personal automobile use. Commentators such as James Howard Kunstler argue that because over 90% of transportation in the U.S. relies on oil, the suburbs' reliance on the automobile is an unsustainable living arrangement. Peak oil would leave many Americans unable to afford petroleum based fuel for their cars, and force them to use bicycles or electric vehicles. Additional options include telecommuting, moving to rural areas, or moving to higher density areas, where walking and public transportation are more viable options. In the latter two cases, suburbia may become the "slums of the future."[143][144] The issues of petroleum supply and demand is also a concern for growing cities in developing countries (where urban areas are expected to absorb most of the world's projected 2.3 billion population increase by 2050). Stressing the energy component of future development plans is seen as an important goal.[145]

Methods that have been suggested[146] for mitigating these urban and suburban issues include the use of non-petroleum vehicles such as electric cars, battery electric vehicles, transit-oriented development, bicycles, new trains, new pedestrianism, smart growth, shared space, urban consolidation, and New Urbanism.

An extensive 2009 report by the United States National Research Council of the Academy of Sciences, commissioned by the United States Congress, stated six main findings.[147] First, that compact development is likely to reduce "Vehicle Miles Traveled" (VMT) throughout the country. Second, that doubling residential density in a given area could reduce VMT by as much as 25% if coupled with measures such as increased employment density and improved public transportation. Third, that higher density, mixed-use developments would produce both direct reductions in CO2 emissions (from less driving), and indirect reductions (such as from lower amounts of materials used per housing unit, higher efficiency climate control, longer vehicle lifespans, and higher efficiency delivery of goods and services. Fourth, that although short term reductions in energy use and CO2 emissions would be modest, that these reductions would grow over time. Fifth, that a major obstacle to more compact development in the United States is political resistance from local zoning regulators, which would hamper efforts by state and regional governments to participate in land-use planning. Sixth, the committee agreed that changes in development that would alter driving patterns and building efficiency would have various secondary costs and benefits that are difficult to quantify. The report made two major recommendations: first that policies that support compact development (and especially its ability to reduce driving, energy use, and CO2 emissions) should be encouraged, and second that further studies should be conducted to make future compact development more effective.

Mitigation

To avoid the serious social and economic implications a global decline in oil production could entail, the Hirsch report emphasized the need to find alternatives, at least ten to twenty years before the peak, and to phase out the use of petroleum over that time,[148] similar to the plan Sweden announced in 2005. Such mitigation could include energy conservation, fuel substitution, and the use of unconventional oil. Because mitigation can reduce the consumption of traditional petroleum sources, it can also affect the timing of peak oil and the shape of the Hubbert curve.

Positive aspects of peak oil

There are those who believe that peak oil should be viewed as a positive event.[149] Many of these critics reason that if the price of oil rises high enough, the use of alternative clean fuels could help control the pollution of fossil fuel use as well as mitigate global warming.[150] Permaculture, particularly as expressed in the work of Australian David Holmgren, and others, sees peak oil as holding tremendous potential for positive change—assuming countries act with foresight. The rebuilding of local food networks, energy production, and the general implementation of 'energy descent culture' are argued to be ethical responses to the acknowledgment of finite fossil resources.[151]

The "Transition Towns" Movement, started in Ireland and spread internationally by 'The Transition Handbook' (Rob Hopkins) sees the combination of peak oil and climate change as an opportunity to restructure society with local resilience and ecological stewardship.[152]

Peak oil for individual nations

Peak oil as a concept applies globally, but it is based on the summation of individual nations experiencing peak oil. Although the most recent International Energy Agency and United States Energy Information Administration production data show record and rising production in Canada and China, in the State of the World 2005, Worldwatch Institute observes that oil production is in decline in 33 of the 48 largest oil-producing countries.[153] Other countries have also passed their individual oil production peaks.

The following list shows significant oil-producing nations and their approximate peak oil production years, organized by year.[154]

- Japan: 1932 (assumed; source does not specify)

- Germany: 1966

- Libya: 1970

- Venezuela: 1970

- USA: 1970[155]

- Iran: 1974

- Nigeria: 1979

- Trinidad & Tobago: 1981[156]

- Egypt: 1987[157]

- France: 1988

- Indonesia: 1991[158]

- Syria: 1996[159]

- India: 1997

- New Zealand: 1997[160]

- Gabon: 1998[161]

- UK: 1999

- Argentina: 1999 (BP statistical workbook 2007)

- Colombia: 1999 (BP statistical workbook 2007)

- Australia: 2000 (BP statistical workbook 2007; A 2007 report by ABARE predicted that production may rise enough for an ultimate peak in 2009[162])

- Norway: 2000[163]

- Oman: 2000[164]

- Mexico: 2004[165]

- Russia: an artificial peak occurred in 1987 shortly before the Collapse of the Soviet Union, but production subsequently recovered, making Russia the second largest oil exporter in the world. Figures from early 2008, statements by officials, and analysis suggest that production may have peaked in 2006/2007.[166][167] Lukoil vice president Leonid Fedun has said $1 trillion would have to be spent on developing new reserves if current production levels were to be maintained.[168]

Peak oil production has not been reached in the following nations (these numbers are estimates and subject to revision):[169]

- Kuwait: 2013

- Saudi Arabia: 2014

- Iraq: 2018

Oil price

In terms of 2007 inflation adjusted dollars, the price of oil peaked on June 30, 2008 at over $143 a barrel. Before this period, the maximum inflation adjusted price was the equivalent of $95–100, in 1980.[170] Crude oil prices in the last several years have steadily risen from about $25 a barrel in August 2003 to over $130 a barrel in May 2008, with the most significant increases happening within the last year. These prices are well above those that caused the 1973 and 1979 energy crises. This has contributed to fears of an economic recession similar to that of the early 1980s.[11] One important indicator that supported the possibility that the price of oil had begun to have an effect on economies was that in the United States, gasoline consumption dropped by .5% in the first two months of 2008,[171] compared to a drop of .4% total in 2007.[172]

However some claim the decline in the U.S. dollar against other significant currencies from 2007 to 2008 is a significant part of oil's price increases from $66 to $130.[173] The dollar lost approximately 14% of its value against the Euro from May 2007 to May 2008, and the price of oil rose 96% in the same time period.

Helping to fuel these price increases were reports that petroleum production is at[5][6][7] or near full capacity.[9][125][174] In June 2005, OPEC admitted that they would 'struggle' to pump enough oil to meet pricing pressures for the fourth quarter of that year.[175]

Demand pressures on oil have been strong. Global consumption of oil rose from 30 billion barrels (4.8×109 m3) in 2004 to 31 billion in 2005. These consumption rates are far above new discoveries for the period, which had fallen to only eight billion barrels of new oil reserves in new accumulations in 2004.[176] In 2005, consumption was within 2 million barrels per day (320×103 m3/d) of production, and at any one time there are about 54 days of stock in the OECD system plus 37 days in emergency stockpiles.

Besides supply and demand pressures, at times security related factors may have contributed to increases in prices,[174] including the "War on Terror," missile launches in North Korea,[177] the Crisis between Israel and Lebanon,[178] nuclear brinkmanship between the U.S. and Iran,[179] and reports from the U.S. Department of Energy and others showing a decline in petroleum reserves.[180]

Another factor in oil price is the cost of extracting crude. As the extraction of oil has become more difficult, oil's historically high ratio of Energy Returned on Energy Invested has seen a significant decline. The increased price of oil makes unconventional sources of oil retrieval more attractive. For example, oil sands are actually a reserve of bitumen, a heavier, lower value oil compared to conventional crude.

Effects of rising oil prices

In the past, the price of oil has led to economic recessions, such as the 1973 and 1979 energy crises. The effect the price of oil has on an economy is known as a price shock. In many European countries, which have high taxes on fuels, such price shocks could potentially be mitigated somewhat by temporarily or permanently suspending the taxes as fuel costs rise.[182] This method of softening price shocks is less useful in countries with much lower gas taxes, such as the United States.

Some economists predict that a substitution effect will spur demand for alternate energy sources, such as coal or liquefied natural gas. This substitution can only be temporary, as coal and natural gas are finite resources as well.

Prior to the run-up in fuel prices, many motorists opted for larger, less fuel-efficient sport utility vehicles and full-sized pickups in the United States, Canada, and other countries. This trend has been reversing due to sustained high prices of fuel. The September 2005 sales data for all vehicle vendors indicated SUV sales dropped while small cars sales increased. Hybrid and diesel vehicles are also gaining in popularity.[183]

In 2008, a report by Cambridge Energy Research Associates stated that 2007 had been the year of peak gasoline usage in the United States, and that record energy levels would cause an "enduring shift" in energy consumption practices.[184] According to the report, in April gas consumption had been lower than a year before for the sixth straight month, suggesting 2008 would be the first year U.S. gasoline usage declined in 17 years. The total miles driven in the U.S. peaked in 2006.[185]

Historical understanding of world oil supply limits

Although the Earth's finite oil supply means that peak oil is inevitable, technological innovations in finding and drilling for oil have at times changed the understanding of the total oil supply on Earth. As scientific understanding of petroleum geology has increased, so has our understanding of the Earth's total recoverable reserves. Since 1965, major oil surveys have averaged a 95% confidence Estimated Ultimate Retrieval (P95 EUR) of a little under 2,000 billion barrels (320×109 m3), though some estimates have been as low as 1,500 billion barrels (240×109 m3), and as high as 2,400 billion barrels (380×109 m3).[6]

The EUR reported by the 2000 USGS survey of 2,300 billion barrels (370×109 m3) has been criticized for assuming a discovery trend over the next twenty years that would reverse the observed trend of the past 40 years. Their 95% confidence EUR of 2,300 billion barrels (370×109 m3) assumed that discovery levels would stay steady, despite the fact that discovery levels have been falling steadily since the 1960s. That trend of falling discoveries has continued in the seven years since the USGS made their assumption. The 2000 USGS is also criticized for introducing other methodological errors, as well as assuming 2030 production rates inconsistent with projected reserves.[6]

Criticisms

Some do not agree with peak oil, at least as it has been presented by Matthew Simmons. The president of Royal Dutch Shell's U.S. operations John Hofmeister, while agreeing that conventional oil production will soon start to decline, has criticized Simmons's analysis for being "overly focused on a single country: Saudi Arabia, the world's largest exporter and OPEC swing producer." He also points to the large reserves at the U.S. outer continental shelf, which holds an estimated 100 billion barrels (16×109 m3) of oil and natural gas. As things stand, however, only 15% of those reserves are currently exploitable, a good part of that off the coasts of Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas. Hofmeister also contends that Simmons erred in excluding unconventional sources of oil such as the oil sands of Canada, where Shell is already active. The Canadian oil sands—a natural combination of sand, water, and oil found largely in Alberta and Saskatchewan—is believed to contain one trillion barrels of oil. Another trillion barrels are also said to be trapped in rocks in Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming,[186] but are in the form of oil shale. These particular reserves present major environmental, social, and economic obstacles to recovery.[187][188] Hofmeister also claims that if oil companies were allowed to drill more in the United States enough to produce another 2 million barrels per day (320×103 m3/d), oil and gas prices would not be as high as they are in the later part of the 2000 to 2010 decade. He thinks that high energy prices are causing social unrest similar to levels surrounding the Rodney King riots.[189]

Dr. Christoph Rühl, Chief economist of BP, repeatedly uttered strong doubts about the peak oil hypothesis:[190]

Physical peak oil, which I have no reason to accept as a valid statement either on theoretical, scientific or ideological grounds, would be insensitive to prices. (...)In fact the whole hypothesis of peak oil – which is that there is a certain amount of oil in the ground, consumed at a certain rate, and then it's finished – does not react to anything.... (Global Warming) is likely to be more of a natural limit than all these peak oil theories combined. (...) Peak oil has been predicted for 150 years. It has never happened, and it will stay this way.

According to Rühl, the main limitations for oil availability are "above ground" and are to be found in the availability of staff, expertise, technology, investment security, money and last but not least in global warming. The oil question is about price and not the basic availability. His views are shared by Daniel Yergin of CERA, who added that the recent high price phase might add to a future demise of the oil industry - not of lack of resources or an apocalyptic shock but the timely and smooth setup of alternatives.[191]

In fiction

Alex Scarrow's novel, Last Light,[192] takes place during a peak oil crisis. The book portrays the collapse of the United Kingdom, as a result of a full-scale terrorist attack against several important key installations in the Middle-East. It follows the experiences of a family, a father trapped in Iraq, a mother far away from her children, a daughter and son fending for themselves, as the complete break-down of law and order causes looting, deaths, and worse.

James Howard Kunstler, author of The Long Emergency[193] and The Geography of Nowhere,[194] fictionalized his predictions of post-oil civilization into a novel entitled World Made by Hand.[195][196] The book portrays the efforts of Robert Earle, a former software executive elected mayor of a small town in New York State, who faces the struggle of rebuilding a civil society amid arguing factions.

Another novel using peak oil for its premise is Robert Charles Wilson's Julian Comstock: A Story of 22nd Century America.[197] set a hundred years after the end of the age of oil, where American society has fallen back to a level similar to that of the Civil War. The book follows Julian Comstock, the nephew of the President, during a series of battles and adventures across an American landscape where many cities have been scavenged for their precious resources.

The Mad Max films are based in a post-apocalyptic Australia, in which (Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior explains) the general social collapse has occurred because of a global energy shortage, particularly of oil.

The 1979 comedy Americathon is set in a future (1998) where the USA has run out of oil and the economy is near collapse. Americans live in their (now stationary) cars and commute by either jogging or riding bicycles.

Frontlines: Fuel of War, a 2008 First-Person Shooter video game for the Xbox 360 and PC, is set during a fictional World War after peak oil occurs.

See also

Prediction

Technology

|

Economics

Others

|

Further information

Books

- Campbell, Colin J (2004). The Essence of Oil & Gas Depletion. Multi-Science Publishing. ISBN 0-906522-19-6.

- Campbell, Colin J (1997). The Coming Oil Crisis. Multi-Science Publishing. ISBN 0-906522-11-0.

- Campbell, Colin J (2005). Oil Crisis. Multi-Science Publishing. ISBN 0-906522-39-0.

- Deffeyes, Kenneth S (2002). Hubbert's Peak: The Impending World Oil Shortage. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09086-6.

- Deffeyes, Kenneth S (2005). Beyond Oil: The View from Hubbert's Peak. Hill and Wang. ISBN 0-8090-2956-1.

- Goodstein David (2005). Out of Gas: The End of the Age Of Oil. WW Norton. ISBN 0-393-05857-3.

- Heinberg Richard (2003). The Party's Over: Oil, War, and the Fate of Industrial Societies. New Society Publishers. ISBN 0-86571-482-7.

- Heinberg, Richard (2004). Power Down: Options and Actions for a Post-Carbon World. New Society Publishers. ISBN 0-86571-510-6.

- Heinberg, Richard (2006). The Oil Depletion Protocol: A Plan to Avert Oil Wars, Terrorism and Economic Collapse. New Society Publishers. ISBN 0-86571-563-7.

- Huber Peter (2005). The Bottomless Well. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-03116-1.

- Kunstler James H (2005). The Long Emergency: Surviving the End of the Oil Age, Climate Change, and Other Converging Catastrophes. Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 0-87113-888-3.

- Leggett Jeremy K (2005). The Empty Tank: Oil, Gas, Hot Air, and the Coming Financial Catastrophe. Random House. ISBN 1-4000-6527-5.

- Leggett, Jeremy K (2005). Half Gone: Oil, Gas, Hot Air and the Global Energy Crisis. Portobello Books. ISBN 1-8462-7004-9.

- Leggett Jeremy K (2001). The Carbon War: Global Warming and the End of the Oil Era. Routledge. ISBN 0415931029.

- Lovins Amory et al. (2005). Winning the Oil Endgame: Innovation for Profit, Jobs and Security. Rocky Mountain Institute. ISBN 1-881071-10-3.

- Pfeiffer Dale Allen (2004). The End of the Oil Age. Lulu Press. ISBN 1-4116-0629-9.

- Newman Sheila (2008). The Final Energy Crisis (2nd ed.). Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-2717-4. OCLC 228370383.

- Roberts Paul (2004). The End of Oil. On the Edge of a Perilous New World. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 9780618239771.

- Ruppert Michael C (2005). Crossing the Rubicon: The Decline of the American Empire at the End of the Age of Oil. New Society. ISBN 978-0865715400.

- Simmons Matthew R (2005). Twilight in the Desert: The Coming Saudi Oil Shock and the World Economy. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-73876-X.

- Simon Julian L (1998). The Ultimate Resource. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00381-5.

- Stansberry Mark A, Reimbold Jason (2008). The Braking Point. Hawk Publishing. ISBN 978-1-930709-67-6.

- Tertzakian Peter (2006). A Thousand Barrels a Second. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-146874-9.

Articles

- Tinker Scott W (2005-06-25). "Of peaks and valleys: Doomsday energy scenarios burn away under scrutiny". Dallas Morning News. http://www.jsg.utexas.edu/news/rels/062505a.html.

- Benner Katie (2005-12-07). "Lawmakers: Will we run out of oil?". CNN. http://money.cnn.com/2005/12/07/markets/peak_oil/index.htm.

- Benner Katie (2004-11-03). "Oil: Is the end at hand?". CNN. http://money.cnn.com/2004/11/02/markets/peak_oil/.

- "The future of oil". Foreign Policy. http://www.foreignpolicy.com/story/cms.php?story_id=3233.

- Robert Hirsch (2008-06). "Peak oil: "A significant period of discomfort"". Allianz Knowledge. http://knowledge.allianz.com/en/globalissues/safety_security/energy_security/hirsch_peak_oil_production.html.

- Didier Houssin, International Energy Agency (2008-05). "Oil: “If you invest more, you find more”". Allianz Knowledge. http://knowledge.allianz.com/en/globalissues/safety_security/energy_security/iea_energy_houssin.html.

- Campbell Colin, Laherrère Jean. "The end of cheap oil". Scientific American. http://dieoff.org/page140.htm.

- Williams Mark. "The end of oil?". Technology Review (MIT). http://www.technologyreview.com/articles/05/02/issue/review_oil.asp.

- Appenzeller Tim. "The end of cheap oil". National Geographic. http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/0406/feature5/.

- Lynch Michael C. "The new pessimism about petroleum resources". http://www.gasresources.net/Lynch(Hubbert-Deffeyes).htm.

- Leonardo Maugeri (2004-05-20). "Oil: Never Cry Wolf—Why the Petroleum Age Is Far from over". Science. http://www.energybulletin.net/node/347.

- Roberts Paul (2004-08). "Last Stop Gas". Harper's Magazine: 71–72. http://www.harpers.org/LastStopGas.html.

- "'Peak oil' enters mainstream debate". BBC News. 2005-06-10. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/4077802.stm. Retrieved 2010-03-26.

- Alex Kuhlman (2006-06). "Peak oil and the collapse of commercial aviation" (PDF). Airways. http://www.oildecline.com/airways.pdf.

- Cochrane Troy (2008-01-04). "Peak oil?: Oil supply and accumulation". Cultural Shifts. http://culturalshifts.com/archives/205.

- Jaeon Kirby & Colin Campbell (2008-05-30). "Life at $200 a barrel". Maclean's. http://www.macleans.ca/business/economy/article.jsp?content=20080528_21002_21002.

Reports, essays, and lectures

- "Crude oil - the supply outlook" (PDF). Energy Watch Group. 2007-10-22. http://www.energywatchgroup.org/fileadmin/global/pdf/EWG_Oilreport_10-2007.pdf.

- "Doctoral thesis: Giant oil fields - the highway to oil: giant oil fields and their importance for future oil production". Uppsala University. 2007-03-30. http://publications.uu.se/abstract.xsql?dbid=7625.

- "Review: Oil-based technology and economy - prospects for the future". The Danish Board of Technology (Teknologirådet). 2005-06-09. http://www.tekno.dk/subpage.php3?article=1025&toppic=kategori11&language=uk&category=11/.

- "The end of oil" (PDF). University of Otago Department of Physics. 2005-07. http://www.physics.otago.ac.nz/eman/The%20End%20of%20Oil%20essay%201.pdf.

- "Australia’s future oil supply and alternative transport fuels". Parliament of Australia - Senate. 2007-02-07. http://www.aph.gov.au/SENATE/committee/rrat_ctte/oil_supply/report/index.htm.

- UK Industry Taskforce on Peak Oil and Energy Security (2010). "The Oil Crunch: Securing the UK's Energy Future". http://peakoiltaskforce.net/download-the-report/2010-peak-oil-report/. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

Documentary Film

- Collapse (film) (2009)

- Crude Awakening: The Oil Crash (2006)

- The End of Suburbia: Oil Depletion and the Collapse of the American Dream (2004)

- PetroApocalypse Now? (2008)

- The Power of Community: How Cuba Survived Peak Oil (2006)

- What a Way to Go: Life at the End of Empire (2007)

Notes

- ↑ A list of over 20 published articles and books from government and journal sources supporting this thesis have been compiled at Dieoff.org in the section "Food, Land, Water, and Population."

References

- ↑ Hubbert, Marion King (June 1956). "Nuclear Energy and the Fossil Fuels 'Drilling and Production Practice'" (PDF). Spring Meeting of the Southern District. Division of Production. American Petroleum Institute. San Antonio, Texas: Shell Development Company. pp. 22–27. http://www.hubbertpeak.com/hubbert/1956/1956.pdf. Retrieved 2008-04-18.

- ↑ Brandt, Adam R. (May 2007). "Testing Hubbert" (PDF). Energy Policy (Elsevier) 35 (5): 3074–3088. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2006.11.004. http://www.iaee.org/en/students/best_papers/Adam_Brandt.pdf.

- ↑ Gwyn, Richard (2004-01-28). "Demand for Oil Outstripping Supply". Toronto Star. http://www.commondreams.org/views04/0128-10.htm. Retrieved 2008-07-27.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "CERA says peak oil theory is faulty". Energy Bulletin (Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA)). 2006-11-14. http://www.energybulletin.net/22381.html. Retrieved 2008-07-27.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Deffeyes, Kenneth S (2007-01-19). "Current Events - Join us as we watch the crisis unfolding". Princeton University: Beyond Oil. http://www.princeton.edu/hubbert/current-events.html. Retrieved 2008-07-27.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 Zittel, Werner; Schindler, Jorg (October 2007) (PDF). Crude Oil: The Supply Outlook. Energy Watch Group. EWG-Series No 3/2007. http://www.energywatchgroup.org/fileadmin/global/pdf/EWG_Oilreport_10-2007.pdf. Retrieved 2008-07-27.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Cohen, Dave (2007-10-31). "The Perfect Storm". Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas. http://www.aspo-usa.com/archives/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=243&Itemid=91. Retrieved 2008-07-27.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Kjell Aleklett, Mikael Höök, Kristofer Jakobsson, Michael Lardelli, Simon Snowden, Bengt Söderbergh (2009-11-09). "The Peak of the Oil Age". Energy Policy. http://www.tsl.uu.se/uhdsg/Publications/PeakOilAge.pdf. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Koppelaar, Rembrandt H.E.M. (September 2006) (PDF). World Production and Peaking Outlook. Peakoil Nederland. http://peakoil.nl/wp-content/uploads/2006/09/asponl_2005_report.pdf. Retrieved 2008-07-27.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Nick A. Owen, Oliver R. Inderwildi, David A. King (2010). "The status of conventional world oil reserves—Hype or cause for concern?". Energy Policy 38: 4743. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2010.02.026.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Bruno, Joe Bel (2008-03-08). "Oil Rally May Be Economy's Undoing". USA Today. Associated Press. http://www.usatoday.com/money/economy/2008-03-08-3190491488_x.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-11.

- ↑ "World oil demand 'to rise by 37%'". BBC News. 2006-06-20. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/5099400.stm. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- ↑ "Petroleum and other liquid fuels" (PDF). 2007 International Energy Outlook. United States Energy Information Administration. May 2007. http://www.eia.doe.gov/oiaf/archive/ieo07/pdf/oil.pdf. Retrieved 2009-07-11.

- ↑ (PDF) Annual Energy Review 2008. United States Energy Information Administration. 2009-06-29. DOE/EIA-0384(2008). http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/aer/pdf/pages/sec1_3.pdf. Retrieved 2009-07-11.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Global Oil Consumption". United States Energy Information Administration. http://www.eia.doe.gov/pub/oil_gas/petroleum/analysis_publications/oil_market_basics/demand_text.htm#Global%20Oil%20Consumption. Retrieved 2008-07-27.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Wood, John H.; Long, Gary R.; Morehouse, David F. (2004-08-18). "Long-Term World Oil Supply Scenarios: The Future Is Neither as Bleak or Rosy as Some Assert". United States Energy Information Administration. http://www.eia.doe.gov/pub/oil_gas/petroleum/feature_articles/2004/worldoilsupply/oilsupply04.html. Retrieved 2008-07-27.

- ↑ "Domestic Demand for Refined Petroleum Products by Sector". United States Bureau of Transportation Statistics. http://www.bts.gov/publications/national_transportation_statistics/html/table_04_03.html. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "International Petroleum (Oil) Consumption Data". United States Energy Information Administration. http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/international/oilconsumption.html. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 (PDF) BP Statistical Review of Energy. BP. June 2008. http://www.bp.com/liveassets/bp_internet/globalbp/globalbp_uk_english/reports_and_publications/statistical_energy_review_2008/STAGING/local_assets/downloads/pdf/statistical_review_of_world_energy_full_review_2008.pdf. Retrieved 2008-07-27.

- ↑ "Oil price 'may hit $200 a barrel'". BBC News. 2008-05-07. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/7387203.stm. Retrieved 2009-07-11.

- ↑ Mcdonald, Joe (2008-04-21). "Gas guzzlers a hit in China, where car sales are booming". USA Today. Associated Press. http://www.usatoday.com/money/economy/2008-04-21-2494500625_x.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-11.

- ↑ O'Brien, Kevin (2008-07-02). "China's Negative Economic Outlook". Seeking Alpha. http://seekingalpha.com/article/83459-china-s-negative-economic-outlook. Retrieved 2008-07-27.

- ↑ "China and India: A Rage for Oil". Business Week. 2005-08-25. http://www.businessweek.com/bwdaily/dnflash/aug2005/nf20050825_4692_db016.htm?chan=gb. Retrieved 2008-07-27.

- ↑ Goldstein, Steve (2009-01-26). "IEA sees first two-year oil demand fall in 26 years". The Wall Street Journal. http://www.marketwatch.com/news/story/iea-forecasts-first-two-year-oil/story.aspx?guid={046FC369-8971-4669-A3E2-F94414A8DA60}. Retrieved 2009-07-11.